GEORGIA: THE ART OF THE CHURCHES

On the road, we quickly realised one thing: Georgia is full of churches. Every village has at least one chapel, but the highest peaks and the most unlikely places are full of them too. Through our experience in the field, we're going to try and tell you a bit about the history of Georgian ecclesiastical architecture.

STONE CULTURE

Louis Dutrieux

8/12/20246 min read

Discovering a style

It's been a few days since we left Batumi, heading for the Inner Kartlia where Torniké Machaidze, a Georgian stonemason, is waiting for us in his workshop in Patara Ateni. The sea is now far behind us, and our calves are warming up as we tackle the Caucasian relief. All around us, the plains are becoming increasingly scarce, and our horizon is now dotted with peaks. During our ascent, in the municipality of Aketi, we stopped near a small church built of brown sandstone, set at the top of a hill. Perched on a mountainside, the church blends harmoniously into the green, almost tropical landscape. As we enter the church grounds, we take care to close the gate to its enclosure, to prevent any stray cows or pigs from interrupting our work. Taking the time to observe the church in detail, we made our first sketches. This moment of study marked the beginning of our encounters with the Georgian churches that we had heard about. We discovered a subtle harmony between oriental-influenced interlacing and elegant sobriety. The decorations around the doors and windows seem to incense the light, while the thick, smooth walls stand as solid as the surrounding mountains.

As we continue our journey through the mountains and valleys of the Caucasus, we discover a Georgian landscape dotted with hundreds of churches and religious buildings, many of them in stone. Whether very old or still under construction, these monuments are an essential part of the country's cultural identity. Not only do they embody the importance of the Orthodox religion in Georgia, but they also offer a special place for the stone trades.

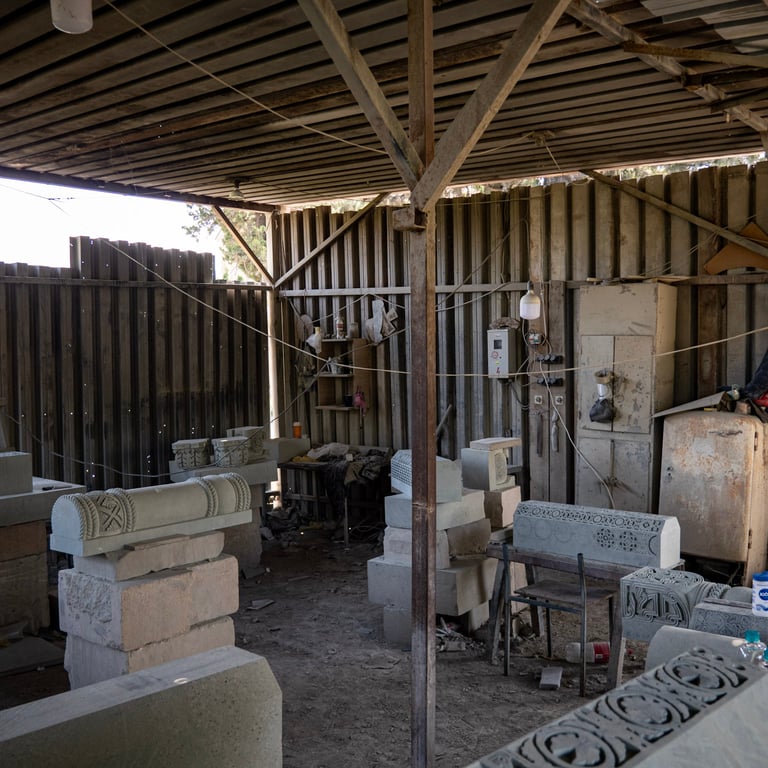

For one month, in the Torniké workshop, we will be cutting sandstone cornices for the construction of a church. The cornices we have to make have a particular moulding profile that we are not familiar with. Because of this break in style, we'll be taking advantage of our colleague's knowledge to learn more about how churches have evolved over time. From the vantage point of the workshop overlooking the village, we'll be spending some fabulous time with Torniké, listening to him describe the stories behind these churches.

A brief history of Georgian churches

From the IVᵉ century onwards, the first consecrated places, intended for Georgian Orthodox worship, were built following a basilical plan inspired by proto-Christian churches. It is characterised by an elongated rectangular shape with double-pitched roofs. In the Vᵉ century, church architecture began to take on Byzantine elements, such as domes and inscribed crosses. A century later, Sassanid¹ influences also appeared, marked by zoomorphic decorations found notably on the church of Bolnisi in the Lower Khartelia region. The construction of domes using trumpets or pendentives also became widespread during this century. In the VIIᵉ century, the Armenian and Georgian autocephalous clergy began to diverge, both dogmatically and architecturally, whereas they had originally been very similar. The dimensions and styles of the ornaments on the buildings continued to evolve mainly until the Mongol invasion from the XIIIᵉ century onwards. The golden age of Georgian medieval architecture then slowly declined after the Mongol invasion. It nevertheless left a lasting imprint, laying down the forms and codes that can still be found today in the existing heritage, and especially in the many churches being built across the country.

During our discussions with Torniké and Goga, it became clear that there is no shortage of work for them. Whether it's for the creation of liturgical furniture, iconostases, columns, cornices or arches, orders for ornate stone products are continuing unabated. The Georgian Orthodox clergy is not just a cult, it is also an important customer for our fellow stonemasons. Indirectly, this church is also helping to preserve traditional skills, by enabling stonemasons and ornamental sculptors to keep in touch with their predecessors. After this month's work and observation with Torniké, we still need to find out how much of the business is in our sector, apart from this church clientele.

Do you like our articles?

Help us by offering a coffee!

²Programm Haussmann*( Article “Apporter sa pierre à l’édifice”)

View of Tbilisi Cathedral

Left and right: Tbilisi Cathedral / Centre: One of the columns on the esplanade of Tbilisi Cathedral.

Visit to Samtredia church. The exterior of this church is almost finished, but it was left to rot in the middle of the building work.

On the way to Patara Ateni, we counted around ten churches under construction. In Gori alone, the largest town near the workshop, we counted three. Some were started decades ago, others have just been completed. Most of them have a concrete or brick structure, veneered with stone around 10 cm thick, stapled to the walls. This construction method is very common in Georgia and reminds us of the buildings we saw in Budapest for the Haussmann² programme. The stone fixtures used are fairly simple. We had the opportunity to see groin vaults cut on an abandoned church site, but apart from this example, round arches and set courses are the most common structures. For most of these buildings, the plans are inspired by medieval churches, and ornamentation can be found around the openings and certain elevations.

To deepen our understanding, Torniké took us to visit Tbilisi's Trinity Cathedral, consecrated in 2004 after a decade of work. On the esplanade is a series of ten pillars that are almost as new as the cathedral itself. They were one of Torniké's first projects. As a young sculptor, he had to help ‘masters’, who, each free to choose their own subjects, could treat the pillar for which he was responsible in their own style. On these bas-reliefs, we can decipher the ‘touch’ of each one. There are Georgian motifs with features influenced by the Soviet style, finely worked figures by a statuary sculptor and elements in an older style. These ten pillars stand out for the freedom of expression in the ornamentation, proof of the mastery of Georgian craftsmen. After these explanations, Torniké takes us to see his master Goga, who works in a workshop behind the cathedral. It's a place that reminds us strangely of the Bauhütte³ we visited in Germany and Austria on our first stopover. Under a sheet metal structure, he shows us the works in progress in speckled green tuff, including an iconostasis⁴ destined for the monastery on Mount Athos in Greece. Amazed by the finesse of this exceptional work, this time we discover first-hand the skill and creativity still alive in the ornamentation present in these Georgian craftsmen.

Know-how tells

³Bauhütte* (Structure dedicated to the construction, maintenance and restoration of a monument and having a specific mode of operation.)

⁴Three-door partition decorated with icons closing the choir where the priest officiates at the consecration.

Samtavissi church, some of the remaining parts of which, such as the one in the central photo and the detail on the right, were built in the 6th century.

Discover the other articles ...

La Route de la Pierre newspaper

Discover the other articles ...

La Route de la Pierre newspaper

Do you like our articles?

Follow the project ...

Editorial by the La Route de la Pierre team

©️La Route de la Pierre | Legal Notice | Privacy Policy | General Terms and Conditions of Sale